China's Gig Economy: Key Data and Insights

The outbreak of COVID-19 and the resulting lockdowns and social distancing measures transformed China's gig economy, particularly highlighting the crucial role of delivery drivers. As millions of people were confined to their homes, often under restrictions, these drivers became a vital lifeline, ensuring access to essential goods. At the same time, e-commerce and online delivery platforms provided much-needed employment for millions of workers suddenly left without jobs. Between January and March 2020, Meituan alone recruited 458,000 new drivers[1] for its food delivery business, underscoring the rapid expansion of the gig economy during this period.

The gig economy, defined as a labor market where individuals engage in short-term, flexible work often facilitated by digital platforms, has grown significantly in China. This shift began in the 1980s with Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, which encouraged self-employment and rural entrepreneurship. The gig economy gained momentum in the early 2000s due to urban migration and layoffs in state-owned enterprises, and further accelerated in the 2010s as businesses and workers sought greater flexibility amid economic shifts.

State policies[2] , such as Premier Li Keqiang's "Internet Plus" strategy introduced in 2015, played a crucial role in sustaining this growth by promoting innovation and entrepreneurship through digital technologies. The rapid expansion of e-commerce, driven by collaborations between the World Bank and Alibaba Group, not only helped lift millions out of poverty but also increased demand for gig work services. As a result, China's gig economy has grown to an estimated value of 3.4 trillion yuan by 2020, with the food delivery sector alone doubling in size to 1.5 trillion yuan by 2024[3] .

The gig economy's expansion has been further fuelled by China's large and increasingly digitalised workforce, with many workers seeking flexible employment options through platforms such as Didi for ride-hailing and Meituan for food delivery. As of today, over 200 million Chinese workers are engaged in gig roles, accounting for about 25% of the country's workforce, according to data retrieved from Statista[4] . This shift represents not just a temporary trend but a fundamental change in how people work and participate in the economy, with projections suggesting that the gig economy could encompass 40% of total employment by 2025.

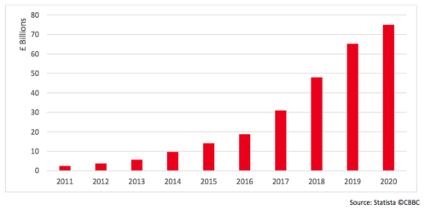

Now, the Chinese gig economy has grown into a multi-billion dollar industry. The food delivery market alone expanded significantly, increasing from £2.4 billion in 2011 to an estimated $75

Figure 1: Market size of the online food delivery business in China, 2011-2020

Decline in appeal for gig workers

This remarkable growth has been driven by a rapidly expanding workforce, primarily consisting of young, male gig workers. Initially, China’s gig industry offered an appealing way to earn money while seeking more stable employment. However, these jobs have increasingly become a fallback option, chosen out of necessity rather than as a steppingstone to socioeconomic advancement. A significant factor contributing to the decline in working conditions is the growing pressure on platforms to turn a profit. Facing intense competition and inspired by Amazon’s business model of relentless expansion, many online delivery and ride-hailing companies initially invested heavily in discounts and premiums to capture market share, often burning through billions of RMB in the process.

For instance, Meituan, which controls 65% of China’s food delivery market, reported losses exceeding £200 million last year, despite a 35% increase in revenue. Similarly, DiDi lost over £1.1 billion in 2020, according to data submitted to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)[1] . However, pressure from investors and the companies’ plans to go public have forced many to cut payments to drivers. Didi Chuxing, raised its commission from drivers to as much as 50% of a ride’s fare, according to a recent report[2] by China’s state media. Similarly, food delivery platforms modified their payment algorithms, reducing the time drivers have to complete an order before facing penalties. A widely circulated report[3] by the state-owned magazine Renwu (人物) highlighted that these changes not only made it more difficult for drivers to earn bonuses, but also heightened the risk of dangerous road accidents. The report cites a study showing a significant increase in the number of fatal road accidents involving delivery drivers between 2017 and 2019.

Increase in demand/orders

Despite the relatively low appeal for the gig economy workers, the demand for deliveries keeps increasing. A 2020 study[4] published in the International Journal of Applied Behavioural Economics examines the motivations of contingent workers in China's gig economy, with a particular focus on the two dominant Mobile Food Delivery Aggregators (MFDA) – Meituan and Ele.me, which control over 80% of the food delivery market in China.

The food delivery market has grown exponentially due to the rapid adoption of MFDAs, now valued at over $37 billion. Food is the top-selling product online, with online food sales increasing by 36.8% year-over-year in the first two months of 2018. China's leading MFDAs have an estimated 355 million users, with the number rising daily. This means that a quarter of the Chinese population orders food via smartphones or other devices. In Beijing alone, over 1.8 million food delivery orders are placed daily, according to data published in the scientific report[5] . Between 2015 and 2016, 63% of online food delivery app users were white-collar workers, and 30.5% were students. Today, 83% are white-collar workers, with only 10% being students. The provinces with the highest demand for online food ordering are Shanghai, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Beijing.

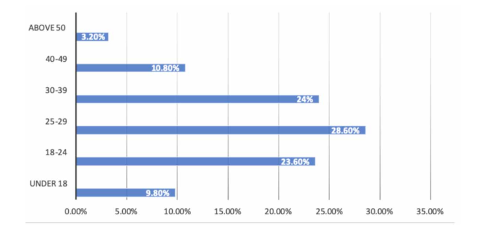

The data in Figure 2 highlights a clear trend in the demographics of food delivery app users in China, indicating that the majority of users are young adults. The largest user base falls within the 25-29 age group, which likely reflects this age group’s busy lifestyles, higher disposable incomes, and comfort with using technology for convenience. The significant representation of the 18-24 and 30-39 age groups further supports the idea that food delivery services are particularly appealing to those in the early stages of their careers or those who value convenience due to work and social commitments. The relatively lower percentages of users under 18 and over 50 suggest that these services are less relevant or accessible to these groups. Younger individuals under 18 may have less financial independence and fewer needs for such services, while older users above 50 might prefer traditional methods of purchasing food or may not be as comfortable with using apps for food delivery. The 40-49 age group, while more represented than the youngest and oldest segments, still lags behind the younger adult population, possibly due to different lifestyle choices or spending habits. Overall, the data underscores that food delivery apps are most popular among young adults in China, particularly those in their late 20s and early 30s, who likely prioritise convenience and have integrated these digital services into their daily routines.

Figure 2: Age distribution of food delivery app users in China (FT, 2019)

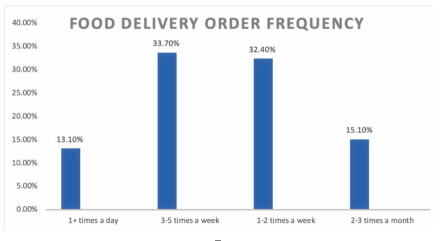

The data presented in Figure 3 highlights the significant reliance on food delivery services among users in China, showcasing how deeply these services have been integrated into daily life. The fact that the largest group of users, 33.7%, orders food 3-5 times a week indicates that food delivery has become a routine part of their weekly activities, likely driven by busy lifestyles and the convenience these services offer. Similarly, the 32.4% of users who order 1-2 times a week further underscores the widespread acceptance and use of food delivery, suggesting that even those who may not rely on it daily still consider it a regular and convenient option. The 15.1% of users who order 2-3 times a month may use delivery services for occasional convenience or special circumstances, while the 13.1% who order more than once a day reflect a small but highly engaged segment that likely uses food delivery as a primary source of meals, possibly due to time constraints, work demands, or personal preferences. Overall, this distribution shows that food delivery services have become an essential part of life for a large portion of the population in China, with many users turning to these platforms several times a week or even daily. This high frequency of use highlights not only the convenience and accessibility of these services but also their growing importance in the urban lifestyle of China’s population.

Figure 3: Food delivery orders - frequency of use (Daxue Consulting, 2019)

Thus, China’s gig economy, which has been growing since the economic reforms of the 1980s, has now become a multi-billion dollar industry deeply integrated into the fabric of urban life. State policies, technological advancements, and a large, digitally savvy workforce have all contributed to this growth, particularly in the food delivery and ride-hailing sectors. The demographic data shows that young adults, particularly those in their late 20s and early 30s, are the primary users of these services, reflecting their busy lifestyles and preference for convenience. However, despite the growth in demand and the economic opportunities provided by the gig economy, the appeal of gig work for many workers has declined. Increasing pressure on platforms to achieve profitability has led to reduced payments and more challenging working conditions for drivers, transforming what was once seen as a flexible and attractive job option into a necessity-driven fallback. As the gig economy continues to expand, with projections suggesting it could account for 40% of total employment by 2025, this sector will remain a cornerstone of China's economic landscape. However, the challenges facing gig workers also highlight the need for a balance between business growth and the well-being of those who drive this economy forward. Ensuring fair compensation and safe working conditions will be crucial as China navigates the future of its rapidly evolving gig economy.