China’s New Retirement Age Reform Explained

On September 13, 2023, the Chinese government announced[1] a significant policy shift: a gradual increase in the retirement age, beginning in January 2025. This marks the first retirement age adjustment since 1950. Currently, China has one of the lowest[2] retirement ages in the world. The top legislative body approved a plan to raise the statutory retirement age for women in blue-collar jobs from 50 to 55, and for women in white-collar jobs from 55 to 58. The changes will be implemented over a 15-year period, starting from January 1, 2025.

This policy shift stems from a comprehensive review of various factors, including life expectancy, population structure, and the health and educational levels of the workforce. China’s pension system faces increasing financial pressure, and the government has recognized the need to adapt its pension and retirement policies to the aging population.

China's Aging Population

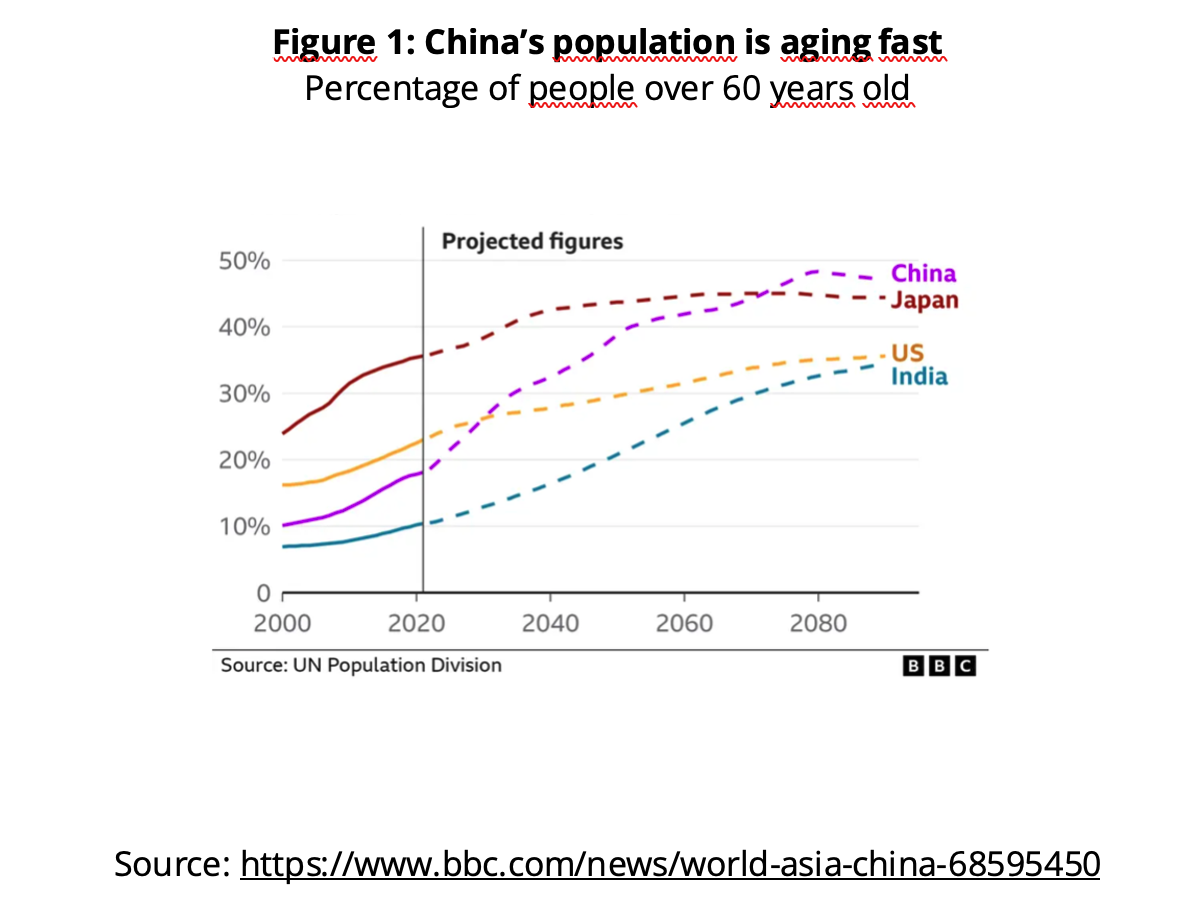

According to data from Reuters[1] , in 2023, China’s population of individuals aged 60 and older climbed to 296.97 million, representing approximately 21.1% of the total population, an increase from 280.04 million in 2022. Furthermore, within the next two decades, China’s elderly population is expected[2] to exceed the entire population of the United States. By 2040, an estimated 402 million people, or about 28% of China’s population, will be over the age of 60, which is currently the legal retirement age for most men in the country, which is illustrated in Figure 1. This data[3] surpasses the anticipated 379 million people in the U.S. by that same year. With the country’s aging population growing at a fast pace, there are growing concerns that the current pension system will struggle to remain sustainable without major reforms.

Pension System

President Xi Jinping has placed a strong emphasis on achieving technological self-sufficiency, hoping that innovations will boost labor productivity and help compensate for potential labor shortages. However, even if these strategies are successful, they will likely not alleviate the mounting financial strain caused by the country’s underfunded social security and pension system. A 2019 influential report[1] by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) warned that as the ratio of workers to retirees continues to shrink, the National Social Security Fund (NSSF)—which was established in 2000 to support future pension obligations—could be exhausted by 2035. Public pension spending already accounts[2] for over 5% of China’s GDP, highlighting the urgent need for changes to ensure long-term sustainability. Therefore, an increase in retirement age could be a successful strategy to tackle this issue.

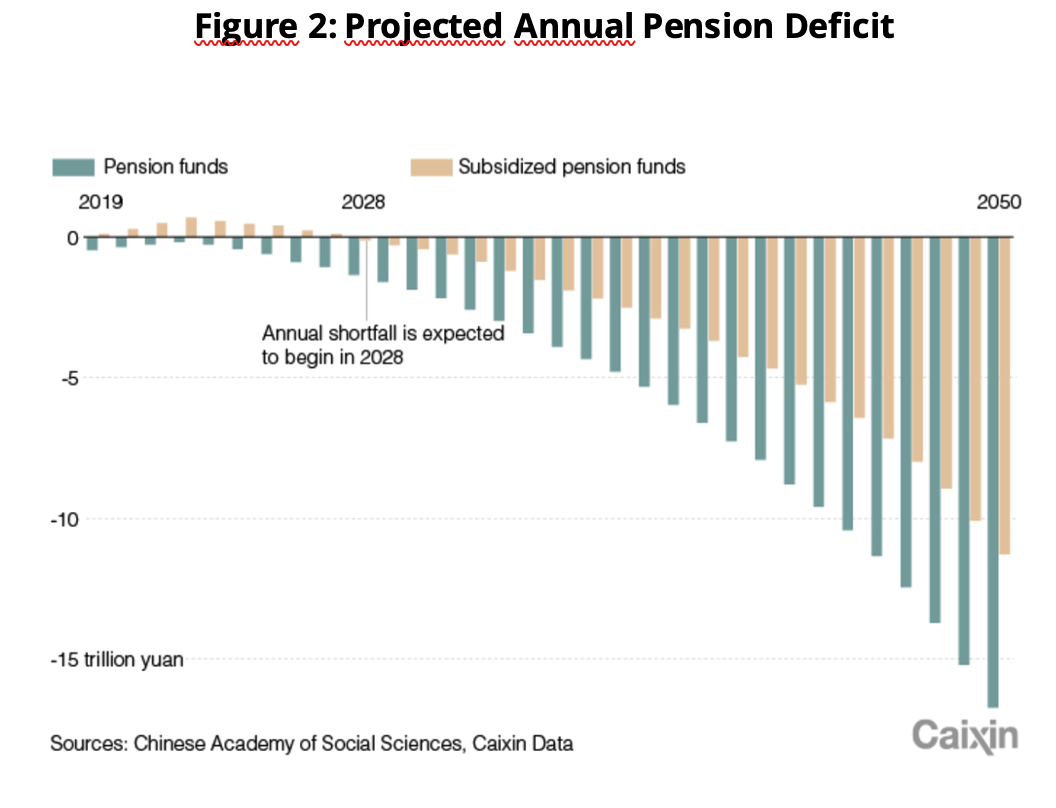

By 2050, the annual pension balance is projected[3] to reach a deficit of 16.73 trillion yuan, which is highlighted in Figure 2. While government subsidies can temporarily delay the pension shortfall, they do not address the underlying issue of the system running out of funds. Despite these subsidies, the pension system is expected to enter an annual deficit as early as 2028, with an estimated shortfall of 118.1 billion yuan, growing to 11.28 trillion yuan by 2050 illustrated in Figure 2. The strain on the pension system continues to mount, as the current ratio of two workers supporting one pensioner is expected to drop to just one worker per pensioner by 2050, according to the CASS report[4] . Figure 3 highlights the projected depletion of pension reserves over time. Starting at around 4 trillion yuan in 2019, the accumulated pension funds gradually increase, peaking at 6.99 trillion yuan in 2027. However, after this peak, a sharp decline begins, with the pension funds expected to drop steadily each year, reaching zero by 2035. This projection[5] underscores the significant financial pressure China’s pension system faces, as demographic shifts and an aging population lead to a rapid depletion of available funds. The data[6] signals an urgent need for reform to prevent the complete exhaustion of pension reserves.

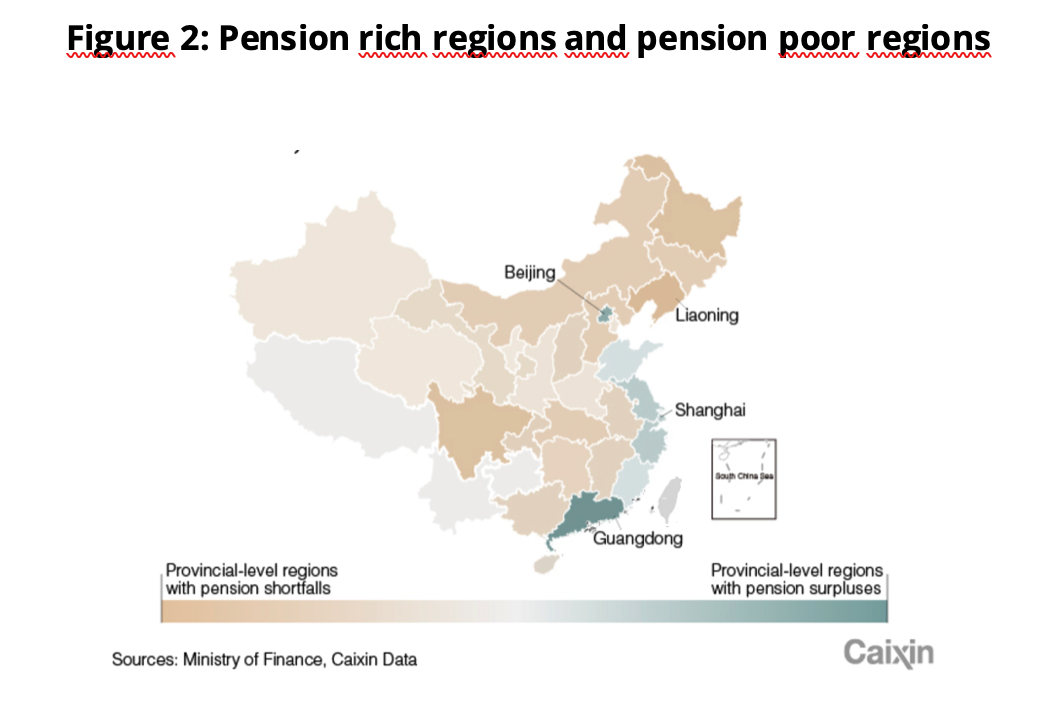

China’s pension system[1] is structured around three primary pillars. The first and most significant is the state-run basic pension system, which forms the backbone of retirement support. The second pillar consists of voluntary employer-sponsored pension plans, while the third is made up of private voluntary retirement schemes. Despite the presence of these additional pillars, experts[2] note that both corporate and private pension plans are still underdeveloped, leaving the public system under considerable financial strain. Unlike many other countries, China’s pension system is administered at the provincial level rather than as a unified national system. This decentralized approach[3] has led to significant regional disparities. Northern provinces, which have experienced weaker economic growth and large population outflows, face the greatest pension deficits. In response, China established a special fund in 2018 to redistribute pension resources from wealthier coastal provinces, such as Guangdong, to struggling regions such as Heilongjiang and Liaoning.

Eleven of China’s 31 provinces are already running pension deficits, according to data[4] from the Ministry of Finance. By the end of 2022, the system covered[5] about 1.05 billion people, with around 350 million still outside the system, primarily younger individuals under 16. However, the system exhibits significant disparities, particularly between urban and rural residents. Urban salaried workers and business owners are eligible for more generous pension plans, while rural and unsalaried urban residents receive much lower benefits. The insurance system combines individual accounts and a basic pension. Urban workers receive[6] an average pension of 3,326 yuan per month ($461), largely funded by employer contributions which covered about 503 million active workers and retirees at the end of 2022. Meanwhile, those under the rural and urban resident plan get an average of just 179 yuan per month (less than $25), primarily funded through taxes and subsidies.

Despite its broad reach, the system[7] faces two major challenges. First, China’s employer pension contribution rate remains high, even after several reductions between 2015 and 2019, straining businesses while lowering pension fund revenues. In 2020, the system recorded[8] its first-ever deficit, forcing the government to dip into the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) to cover shortfalls. The second challenge[9] is the fragmented administration of the pension system, which is managed at the provincial level. Wealthier provinces such as Guangdong can afford lower contribution rates and attract more investment, while poorer provinces such as Heilongjiang struggle to meet pension obligations, sometimes relying on debt to fund payments, which is illustrated in Figure 2. This disparity creates a complex policy dilemma for the government, as lowering employer contribution rates to support businesses may further weaken the sustainability of pension funds.

To align with regional counterparts such as Japan and South Korea, where retirement ages are set at 65 and 63, respectively, China is moving toward similar reforms to address these looming demographic and financial challenges. By encouraging people to stay in the workforce longer, China aims to ease some of the strain on its pension system. However, these changes must be balanced with the need to ensure sufficient employment opportunities for younger generations entering the labor market.