The Origins of Christmas in China

China, a land with a rich tapestry of cultural inventions, has been linked to numerous historical firsts—some more plausible than others. However, one might find it surprising that Christmas, a cornerstone of Western tradition, has its own unique tale woven into the fabric of China's history.

The journey begins in the eighth century with the esteemed poet Li Bai (李白), whose writings mention a celebration called 圣诞之节 (Shèngdàn zhī jié). This term bears a striking resemblance to the modern Chinese word for Christmas, 圣诞节 (Shèngdànjié). However, before one imagines Christmas lights in ancient Chinese cities, it's essential to understand that the roots of Christmas in China are, much like the mythical city of Shangri-la, confined to the realm of names.

The Christian holiday only gained widespread recognition as Shengdanjie in the 1920s, with shengdan (圣诞) signifying the "birth of a saint." Historically, shengdan was a term applied to various celebrations, including the birthdays of Chinese emperors, Daoist idols, and even Confucius—a "saint" mentioned in Lu Xun’s (鲁迅) essay “Shengdan Well-Wishes in Hong Kong (《述香港恭祝圣诞》)” from the late 1920s.

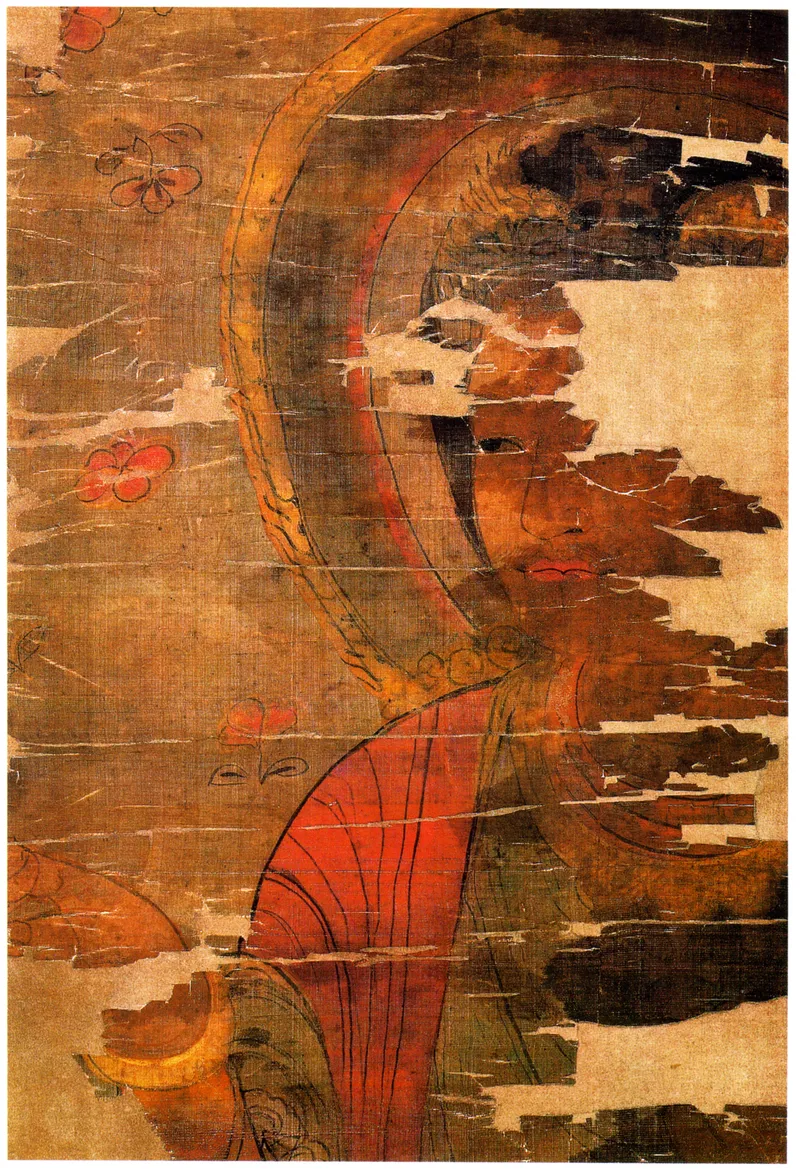

However, the Christmas story in China dates back further than one might anticipate. Li Bai's Shengdanjie, although not celebrated on December 25, coincided with a cosmopolitan era of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). It was during this time that records of Christ's birth celebrations were etched into the Nestorian Stele, an ancient stone monument discovered in 1623 in Chang'an (modern-day Xi’an), the former capital of the Tang dynasty.

The Nestorian Stele narrates the introduction of Christianity to China by the Syrian missionary Alopen in 635. A church was established in Chang'an, and the community expanded into other cities. The Stele, erected in 781 during the reign of Emperor Daizong, reveals special gifts bestowed on the church during "incarnation day" or Christmas.

However, as time marched on, religious groups, including the Nestorians, retreated underground in the mid-800s due to the Tang court's growing concerns about the influence of churches and temples. It wasn't until the 16th century that Christians returned to China, this time with Jesuit priests during the Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1616 – 1911) dynasties.

A noteworthy Qing experience with Christmas occurred in 1868 when Zhang Deyi (张德彝), a government official on a diplomatic mission to Great Britain, recorded a Victorian Christmas celebration in his diaries. The detailed observations of cultural practices provide a fascinating glimpse into the cultural differences of the time.

Christmas festivities, as described by Zhang, included lit-up Catholic and Christian churches, music echoing through the streets, closed shops, and families adorning small trees with toys and candles. This cultural exchange continued with other government officials on diplomatic missions, such as Liu Xihong (刘锡鸿) describing an "old man" distributing gifts in Germany and Zhang Yinhuan (张荫桓) documenting a Christmas party in the United States in 1877.

Foreign communities, established with the arrival of missionaries and treaty ports, embraced Christmas, often coinciding with the traditional Chinese festival of Dongzhi (冬至) or Winter Solstice. Shanghai's Shenbao newspaper, in 1872, referred to Christmas as the "birth of Christ" and later adopted the term "Shengdanjie" in the 1920s.

The late 19th to early 20th centuries witnessed large Christmas celebrations in expatriate communities in Ningbo and Yingkou, and by the early 1900s, Christmas had transitioned from foreign concessions to a public celebration in Shanghai. Christian churches and the YMCA hosted concerts, pageants, and revelry for students and youths across the city.

Despite the cultural exchange, Christmas faced opposition during anti-Christian campaigns following the May 30th Movement in 1925. Yet, Shenbao persisted in running Christmas ads, and holiday parties continued into the wartime 1930s and '40s. However, even amidst the Japanese occupation in 1943, Shenbao criticized the festive revelry, emphasizing the stark reality of the times.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, Christmas persisted in a limited capacity at religious institutions until its return as a public celebration in 1980. A Shanghai YMCA Hotel Christmas concert marked this resurgence, though described as a low-key affair with a simple offering of cake and pastries. In 1992, the Shanghai Peace Hotel hosted its first Christmas dinner and fashion show.

Today, Christmas has become an integral part of China's festive landscape. Decorations adorn major cities, and the country produces a significant share of global Christmas decorations. While China may reject Christianity politically and culturally, it has embraced Christmas as a celebration rooted in "common people’s consumption and enjoyment," as historian Tang Zhenchang (唐振常) aptly observed. Shanghai's adoption of Western cultural practices reflects a progression from surprise to wonder, envy, and ultimately, adoption—a testament to the enduring allure of Christmas in the East.

Sources: Wikipedia, theworldofchinese.com

Author: Jonathan Xu